Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Melismos

The music is an Invocation to the Muse. Translation: 'Sing for me, dear Muse, begin my tuneful strain; a breeze blow from your groves to stir my listless brain' and 'Skillful Calliope, leader of the delightful Muses, and you, skillful priest of our rites, son of Leto, Healer-god (paean) of Delos, be at my side' (J. G. Landels).

Hang on for a haunting ending on the frame drum.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

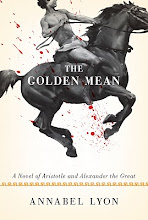

Creating Character: Alexander

Alexander The Great

Originally uploaded by Philippe C.

I knew I wanted the kid to be annoying. There's a reverent literary tradition around Alexander, beginning with his first biographers (Arrian, Plutarch), through the so-called Alexander Romances of Medieval times (where he often had superpowers), right up to the present (most recently with Oliver Stone's 2004 biopic Alexander, featuring Irish heartthrob Colin Farrell).

But years as a teacher have taught me that teenagers with brains and talent are often the most arrogant, insecure, and impossible students of all. I wanted to create a character who would both defy expectations and be immediately recognizable to anyone who's ever had to deal with an exceptionally bright, difficult teenager. I pictured the young Alexander as an annoying narcissist who needed to be taken down a few notches. Just the job for my fictional Aristotle, whose brilliance I much preferred (in the beginning, anyway) to Alexander's brawn.

But I struggled. Early readers told me they believed Alexander as an annoying teenager but couldn't see the seeds of the man who would conquer the world. The more I thought about him, the more he bothered me. I knew he needed to be more than just a smart-aleck, but I still couldn't buy into the tradition of the sexy, hotheaded military genius.

The penny finally dropped when I read an article in the September 29, 2008 New Yorker about an Iraq war veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (William Finnegan's "The Last Tour"). I was struck by the symptoms Finnegan described--headaches, nightmares, alcoholism, loss of touch with reality, and most of all the paradoxical desire to be at home when you're at war and at war when you're home. These symptoms fit the later Alexander (an alcoholic given to fits of blinding violence immediately followed by crippling depressions, who left home at 19 and never returned).

The more I thought about the boyhood that must have preceded this tormented life, the more I wondered if the trauma might have begun very early indeed. His parents by all accounts hated each other. His father took numerous wives and produced half-siblings often enough to keep the young prince's expectations about his future off-balance. His mother was suspected of witchcraft. Alexander was trained as a child soldier, leading troops into battle when he was only 16.

Child soldiers exist today, and we know what damage and trauma they suffer (when we allow ourselves to think about them at all). An ancient child would have suffered no less. Once I understood that, I understood how to proceed with the character I now cared and feared for as much as anyone in the novel.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Aristotle's birthplace

The Athenians never considered Aristotle one of their own. Though he spent the last twelve years of his life living and teaching in Athens, he was forced to leave the city after Alexander's death, when Athenian sentiment turned against anyone associated with Macedon. Aristotle is supposed to have said he didn't want "the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy", a reference to Socrates' execution.

Here's a 30-second clip of the ruins of Stageira:

Tuesday, April 7, 2009

And Now, Some Recipes

He found a drink made of a mixture of grape wine, barley beer and honey mead. (In both the Iliad and the Odyssey, Homer describes a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey, and goat cheese). Small jars contained fatty acids and lipids associated with sheep or goat fat; phenanthrene and cresol, suggesting the meat was barbecued before it was cut from the bone; gluconic, tartaric, and oleic/elaidic acids implying the presence of honey, wine and olive oil respectively (perhaps a marinade?); and a high-protein pulse, likely lentils. Traces of herbs and spices completed the dish.

Despite its far-reaching spider web of trade routes (particularly in the wake of Alexander's great Eastern campaigns), the ancient world was made up largely of locavores. (We moderns think we're so trendy!) A typical Macedonian diet in Aristotle's time would have featured a lot of bread and fish, and seasonal fruits and vegetables. (Both Alexander and his father, Philip, were supposed to have had a passion for apples).

Meat was a luxury unless you were extremely wealthy. Goat and mutton were most common; chicken, duck, goose, and rabbit were also available; beef was rarely eaten. Staple proteins were beans, eggs, cheese, yoghurt, and nuts. Wine was brewed far stronger than we know it today and was usually served with water, as we'd serve scotch. Barley beer was popular in Macedon, less so in warmer, sunnier southern Greece, where grapes were more plentiful.

Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon's Vancouver-centric The 100-Mile Diet: A Year of Local Eating was surprisingly helpful when I tried to picture an ancient kitchen. It made me think about all the foods I took for granted that Aristotle would never have heard of (black tea, coffee, mangoes, sugar, pepper, salmon, chocolate, etc.). It also made me think hard about food storage and seasonal availability; at one point I caught myself giving my characters a meal of roast lamb in autumn--whoops. In the final draft, they get goat.

Historical novelists like to describe food. It's a double urge, I think: to surprise the reader with the sophistication of the era they're describing, and to make the period instantly accessible. How hard is it to imagine sitting down to a plate of feta and walnuts, or a nice, spicy lamb-lentil stew and a beer?

A couple of websites featuring approximations of ancient Greek recipes are ancientgreekfood.net and greek-recipe.com.

Saturday, April 4, 2009

Ten Uses for a Philosophy Degree

2. Go to graduate school. You're never going to get a real job.

3. Go to law school. Oh, thank god, thank god, she's come to her senses. She says those logic courses helped her with the LSAT and having studied ethics might be a real advantage. No, of course I didn't tell her that. You want to put her off before she's even started?

4. Become a nihilist. You dropped out of law school? After one year? What do you mean, you're depressed? We're all depressed! But they'll take you back, right, when you come to your senses? And put that black t-shirt in the laundry, my god, don't you own any other clothes? Don't you want a pension and dental? What is the matter with you?

5. Laugh extra hard at that Monty Python sketch about the all-Bruce philosophy department at the University of Walamaloo (Australia, Australia, Australia, we love you!).

6. Fan yourself with it while imagining you're Lasthenea of Mantinea or Axiothea of Phlius, the only women known to have attended Plato's Academy.

7. Get an MFA in Creative Writing. So, graduate school after all. Which is more useless, do you think, philosophy or creative writing? Hmmm?

8. Read your old textbooks when you feel stressed. Seriously, you do that? Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics? Seriously?

9. Get a job in spite of it. Teaching writing? Do you get a pension and dental with that?

10. Write a novel about Aristotle. I began The Golden Mean in late-September 2001. Like many other privileged North Americans in the arts, I was questioning the relevance of my work in the aftermath of the attacks in New York and Washington. I struggled to read and write fiction, but found some solace in Aristotle. The things he thought about 2300 years ago--what makes a good government? what's a tragedy? what does it mean to lead a good life?--were the things everyone was suddenly thinking and talking about. For me, his words were serious, intelligent, contemporary, alive.

One day I read the thumbnail bio in the front of my copy of his Ethics and found myself wondering--just wondering, really. What would he have made of contemporary political polarities? What did he eat for breakfast? Did he like teaching? Why the particular interest in marine biology? How did he meet his wife?

Finally, I realized the only way I would ever find my way back to the abiding worth of fiction was through this most challenging, engaging, and relevant of subjects.

Friday, April 3, 2009

Aristotle's Thought, Sort Of

(This is the first of three clips from the same lecture, all available on Youtube.)

Thursday, April 2, 2009

All the Life You Can Fit on a Postage Stamp

Vienna, Museum of Art History, Collection of Classical Antiquities. Head of Aristotle.

Originally uploaded by sssn09

From the ocean of historical knowledge, what's known for sure about Aristotle's life would fill a thimble. Good news for this fiction writer (though some historical novelists seem to thrive on a wealth of detail - I'm thinking of Colm Toibin's The Master, inspired in no small part by Leon Edel's five-volume life of Henry James).

The bare bones are these: Aristotle was born in 384BCE in Stageira, Thrace. His father, Nicomachus, was physician to the king of Macedonia, and one can assume both from Greek custom and from Aristotle's subsequent writings that he absorbed a lot of knowledge of his father's trade. It's likely that at this time Aristotle met Philip, the future king of Macedon, then a teenager like himself. From Aristotle's will we know he had a sister and brother, Arimneste and Arimnestus. Arimneste had a son, Nicanor; Arimnestus died childless.

At seventeen, Aristotle went to Athens to study at Plato's Academy. He remained there for almost twenty years, first as a student and later as a teacher, leaving only after Plato's death.

He then spent some years in Asia Minor under the patronage of Hermias of Atarneus. In 343 or 342BCE Aristotle went to Pella, the Macedonian capital, to tutor Philip's son, Alexander. He remained in and around Pella for about seven years, until Philip's murder and Alexander's ascent to the Macedonian throne.

Aristotle then returned to Athens to head the Lyceum, a rival school to the Academy. He remained there for another twelve years or so, until Alexander's death, when Athenian sentiment turned against anyone with Macedonian connections. Aristotle then left Athens for Chalcis, which offered the protection of a Macedonian garrison. He died there a few months later.

As for Aristotle's love life, we know (again from his will) that he had a wife, Pythias, who bore him a daughter, also named Pythias. He also had a companion named Herpyllis, who bore him a son named for his father, Nicomachus. In his will, Aristotle makes affectionate provision both for Herpyllis and for the marriage of his daughter to his sister's son, Nicanor. He also provides for his many slaves. He asks that his own bones be laid with those of his dead wife, "in accordance with her own wishes".

So what's a fiction writer to make of all this? Twenty years at the Academy; another twelve at the Lyceum. Years of genius, all of them; but an explosive life of the mind can look suspiciously like a man sitting quietly in a comfortable chair, staring at his lap. Not promising material for a novel (unless you're Colm Toibin!), so I chose to focus on the seven tumultuous years Aristotle spent at the Macedonian court.

The image above is a Roman copy, mid-1st century, of a Greek original ca. 320BCE.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Welcome!

When I began writing this novel, in 2001, I didn't imagine it would take eight years to finish. Though I guess I should have known: my first book, Oxygen, took six years; my second book, The Best Thing for You, took five; and my children's book, All-Season Edie, took a ridiculous twelve years from start to finish. (Admittedly with some long periods of inactivity in there!) But I thought for sure this one would go faster. Because it was a novel, a form new to me, I planned a meticulous outline, scene by scene, and stuck to it like a terrier. Because I wrote most of the book while pregnant (twice) and/or caring for small children, I set myself targets: 200 words while they nap! Go! And slowly, slowly, paragraph by paragraph, scene by scene, the novel accreted. My embryonic first draft of thirty pages or so eventually became two hundred plus, and then the process of revision began. Ten or so drafts later (you think I'm kidding?), my editor gently suggested I let the book go. It's now set to hit the world on August 25, 2009. I hope this blog will spark interest in Aristotle and his relationship with the young Alexander the Great, and perhaps lead to some discussion of his relevance to the modern world. Welcome!